On April 7, 2021, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals rendered its long-awaited opinion in Gil v. Winn-Dixie Stores, Inc., reversing a trial court’s decision against Winn-Dixie, holding that websites are not places of public accommodation under Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and that Winn-Dixie’s website does not violate 42 U.S.C. § 12182(b)(2)(A)(iii). Most significantly, the court created a major circuit split that may attract the attention of the Supreme Court of the United States when the Eleventh Circuit rejected the “nexus” standard of liability accepted by several other circuits, including the Third and Ninth Circuits, and the plaintiff-friendly, virtual “places of public accommodation” standard accepted in the First, Second, and Seventh Circuits. The opinion is sorely needed good news for retailers facing a deluge of website accessibility lawsuits. Whether it is cause for celebration remains to be seen.

Background

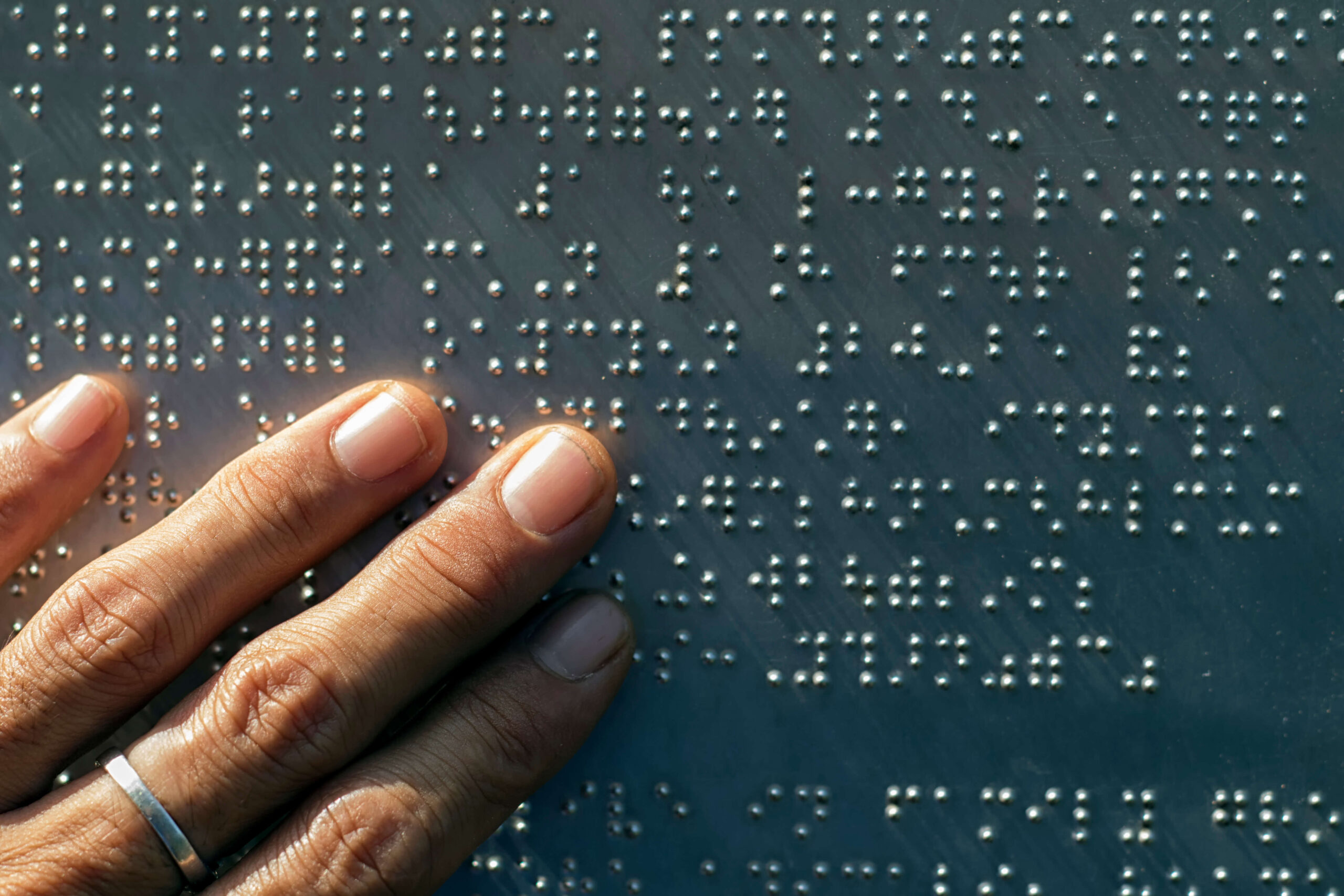

In 2016, plaintiff Juan Carlos Gil sued grocery chain Winn-Dixie, alleging that the grocer had violated the ADA because its website was inaccessible to individuals with visual impairments who use screen-reader software to access the website. Gil claimed he was unable to refill existing prescriptions and link to digital manufacturer coupons available online.

Winn-Dixie argued that Title III did not apply to its website because a website is not a physical “place” of public accommodation within the meaning of Title III and that the website’s alleged lack of accessibility did not prevent Gil from accessing the goods and services of the physical grocery store that is a “place of public accommodation.” After a bench trial, the district court entered judgment in favor of Gil, reasoning that the website was “heavily integrated” with Winn-Dixie’s physical stores, thus “operate[d] as a gateway to … Winn-Dixie’s physical store locations.”

While welcome, Winn-Dixie’s appeal left businesses open to continued and proliferating attacks until the Eleventh Circuit rendered its decision.

The Eleventh Circuit’s Decision

In a 2–1 opinion, the court first held that a website itself is not a “place of public accommodation” under Title III, a position adopted by the lower courts in the First, Second, and Seventh Circuits, where a virtual business behaves like one of the brick-and-mortar “places” of public accommodation listed in the statute. Perhaps more importantly, the court also held that Winn-Dixie’s website did not constitute an “intangible barrier” to Gil’s ability to access and enjoy fully and equally “the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations of any place of public accommodation”—in this case, Winn-Dixie’s grocery stores. A website’s inaccessibility, the court held, will create liability only where that inaccessibility impairs use of the actual “place” of public accommodation. In so ruling, the Eleventh Circuit explicitly rejected the looser “nexus standard” adopted by the Third and Ninth Circuits, which requires a lesser showing of some connection between website content and the physical place.

The dissenting judge cautioned that “the majority opinion gives stores and restaurants license to provide websites and apps that are inaccessible to visually-impaired customers so long as those customers can access an inferior version of these public accommodations’ offerings [at a physical store].”

Key Takeaways

So, does this ruling mean that the flood of website accessibility lawsuits will subside? Probably not. Most significantly, since many businesses and certainly their websites typically reach into multiple jurisdictions, relief in the Eleventh Circuit will not bring immediate relief in many other judicial circuits. But the Eleventh Circuit’s decision does sharpen the conflict between the circuits by setting out a third standard for liability. Such conflicts are often used by litigants to persuade the Supreme Court to accept cases that will resolve the conflicts. Short of action by the U.S. Congress or the U.S. Department of Justice to clarify the applicability of these laws to websites, only a Supreme Court decision is likely to bring greater clarity to this area of law, which clarity businesses may welcome no matter how the Supreme Court may rule.

Even in the Eleventh Circuit, it is unclear how the court’s decision will impact pending and future litigation. The court stressed that Winn-Dixie’s website was “limited use” because it did not impact the use of the grocery store itself, which may not be the case for other websites. In addition, the court noted, and “[m]ost importantly, it is not a point of sale; all purchases must occur at the store.” This suggests that the court may reach a different conclusion in a case involving a website offering online sales. The circuit’s district courts will now be tasked with applying this decision to websites that are not “limited use” and offer direct sales.