The decades-long battle over union security faces two important pivot points during the summer of 2018. On June 27, 2018, the Supreme Court of the United States handed unions a major defeat in the season’s first major fight. With its 5-4 decision in Janus v. AFSCME Council 31, the Court prohibited union security in the public sector, even in the form of “fair share” fees aimed at representational expenses, as impermissible violations of the First Amendment. Meanwhile, in Missouri, an August vote could tip the national scales in favor of right-to-work legislation in the private sector.

Janus

The Court’s Janus decision culminates a long, slow march towards the prohibition of union security in the public sector. In summary:

- 1956-1963: The Supreme Court first confronted compulsory union dues in Railway Employees’ Dept. v. Hanson, and first examined their First Amendment implications in Machinists v. Street. The Street Court found that union security itself does not violate the First Amendment in the private sector. Instead, the Court allowed unions covered by the Railway Labor Act to collect fees supporting negotiation and contract administration expenses. On the other hand, it prohibited compulsory fees supporting costs such as political activities. In NLRB v. General Motors, the Court applied this standard to the vast majority of private-sector employees covered by the National Labor Relations Act.

- 1977: The Court first addressed the First Amendment implications of union security for public-sector employees in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education. There, the Court extended its Street and General Motors holdings to the public sector. As in Street and General Motors, the Abood Court permitted compulsory dues for the purpose of contract negotiation and administration expenses, but disallowed compulsory dues supporting “ideological causes.” For the first time, it found the First Amendment imposed this limitation on the use of dues in the public sector. The Court reasoned that public sector employees possess a property interest in their jobs, and governmental actors cannot deprive them of that interest due to a refusal to support unions’ ideological causes.

- 2016: The Abood decision raised significant questions about the distinction between political and non-political activities in the public sector. For example, if a public entity spends money on higher wages in a union contract, doesn’t that expenditure present a public policy question? The Court appeared set to address these questions, and likely overturn Abood, in its 2016 Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association case. However, Justice Scalia passed away prior to the issuance of a decision. As a result, the Court issued a deadlocked 4-4 decision, resulting in maintenance of the lower courts’ decisions relying on Abood’s validity.

Janus presented the Court with its first opportunity to overturn Abood following Justice Gorsuch’s replacement of Justice Scalia. In its 5-4 decision authored by Justice Alito, the Court held in no uncertain terms that all public sector union activities, not just those identified as “ideological,” implicate the First Amendment. Consequently, unions may not require that public-sector employees pay dues as a condition of employment.

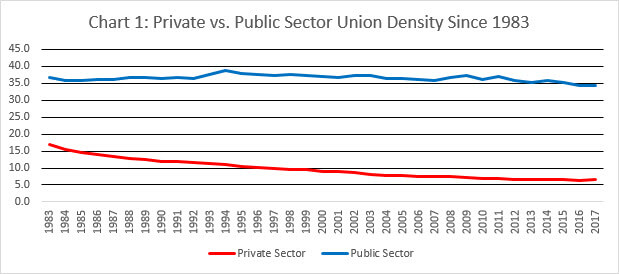

This decision deals a major blow to organized labor. While private-sector union density has declined precipitously over the last quarter-century, from 16.8 percent in 1983 to 6.5 percent in 2017, public-sector union density has remained relatively stable, and currently stands at 34.4 percent. See Chart 1: Private vs. Public Sector Union Density Since 1983

As a result, nearly half (7.2 million) of the 14.8 million union members in the United States work in the public sector, even though the private sector employs approximately five times as many workers. Due to Janus, all 7.2 million of those public sector employees now work in a right-to-work environment as a matter of federal constitutional law. Moving forward, unions must convince those public employees to pay dues as a matter of individual choice, rather than compulsion.

Missouri Right To Work

While Janus represents the capstone of decades of legal advances on public-sector union security issues, in only two months the Show Me State may provide right-to-work advocates with a significant milestone in the private sector. If Missouri voters approve of right-to-work legislation on August 7, 2018, then, for the first time, the majority of private-sector U.S. workers will work in right-to-work states.

Congress gave states power to enact right-to-work legislation when it amended the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) with the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. Taft-Hartley added Section 14(b) to the NLRA, thus permitting states to enact measures prohibiting union security clauses. Section 14(b) is the only explicit portion of the NLRA that exempts state laws from pre-emption. Now, 27 states maintain right-to-work statutes and/or state constitutional provisions. Kentucky became the 26th right-to-work state in 2016, meaning that, for the past two years, a majority of states have prohibited union security. See Chart 2: Number of Right to Work States Since 1943.

However, due to population differences, the 60.5 million workers in right-to-work states comprise only 48.45 percent of the private-sector U.S. workforce. States (and the District of Columbia) that have not adopted right-to-work legislation constitute 49.59 percent of that workforce. Missouri’s 2.4 million private sector workers represent the remaining 1.96 percent. If Missouri becomes a right-to-work state, that percentage would be sufficient to push right-to-work legislation over the 50 percent mark for the first time in history.

Missouri’s political leadership attempted to effectuate this outcome when its General Assembly passed, and former governor Eric Greitens signed Senate Bill 19 on February 6, 2017. Had it taken effect on August 28, 2017, as intended, Missouri would have become the nation’s 28th right-to-work state. However, the state’s unions took advantage of Missouri’s referendum process. By filing sufficient signatures with Missouri’s secretary of state on August 18, 2017, the unions staved off implementation of the bill until and unless voters approve of it at the ballot box.

On May 17, 2018, the General Assembly scheduled the referendum vote for August 7, 2018. If the majority of Missouri voters ratify the legislature’s right-to-work statute, union security will no longer apply to the majority of U.S. workers. If the voters reject the right-to-work legislation, the prospects for right-to-work in Missouri will dim significantly. In that scenario, the next state that moves toward right-to-work status will likely have the opportunity to push the private sector U.S. workforce over the 50 percent threshold, unless population shifts accomplish that task first.

The State Of Union Security

Faced with an inability to compel union dues of any variety in the public sector, coupled with the potential for yet another state joining the right-to-work movement, many unions must now contemplate the sustainability of their revenue streams. The inability to compel dues payments from large swaths of otherwise unwilling workers will inevitably leave a major dent in the unions’ balance sheets. Those consequences, in turn, could result in fewer organizing campaigns and arbitrations, less robust political advocacy, and more cooperative approaches overall. On the other hand, unions will face more pressure to convince workers to voluntarily pay dues, whether by highlighting the purported benefits of unionism, or through social pressure against “free riding.”

Regardless of the labor movement’s practical responses, the summer of 2018 already represents the lowest point for union security since Taft-Hartley’s enactment in 1947. Depending on the preferences of Missouri voters, that nadir may only deepen. Further right-to-work developments merit close observation, as does the labor movement’s responses to union security’s continued decline.